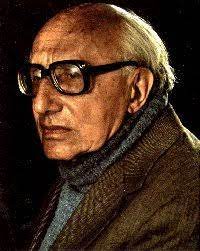

Elias, Norbert

Bio: (1897-1990) German-British sociologist. Norbert Elias received his doctorate in philosophy from the University of Breslau (now Wroclaw, Poland), and then studied sociology at the University of Heidelberg. After that, he was an assistant to Karl Mannheim at the University of Frankfurt for several years. He then emigrated from Germany, due to the coming to power of the Nazi Party. Elias spent almost two decades in the UK, before receiving his first formal academic position at the University of Leicester, and then lectured at the universities in Ghana, Frankfurt, the Netherlands, and others.

Process Sociology

He worked on his habilitation thesis at the University of Heidelberg, which was defended in 1933 but was first published in 1969. It is entitled The Court Society (2006, in German 1969) and in it, Elias outlines the basics of his sociological approach, which he set out in detail in the book On the Process of Civilization (2006, in German 1939a, first translation in English was published in two volumes under the name The Civilizing Process, 1969, 1982). This sociological approach is sometimes called "figurational sociology", although Elias himself preferred to call his approach "process sociology".

The basic premise of process sociology is an attempt to overcome the dualism and antagonism that exists between individuals and society in sociological thought. All people are part of the relationship of interdependence, that is, "figuration" in Elias's terminology. These figurations are in the process of constant emergence and cannot be reduced to the motivations or activities of individual actors. The figurations are constantly changing, and their long-term development is mostly unplanned. The figurations shape the development and life path of each individual. Figurations are processes that create „interweaving” of individuals, that is, they create multiple connections and interrelations between people. Figures do not act as external structures that shape individual behavior, instead, open and interdependent individuals, and their relationships, create figurations. Power relations are central to the development of figurations, and power within figurations lies in the constant swaying around the equilibrium. The figurations work on both the macro and micro levels and encompass every social phenomenon. What connects different figurations are “chains of interdependence”, although individual figurations can be distant and isolated, there is always a connection between them, and that connection is achieved through various chains of interdependence.

Elias believes that sociology is dominated by the idea of what he calls homo clausus, by which he means the idea of closed and isolated individuals. Elias opposes this view, and he states that all people are open, and constantly connected to other people through complex relationships. In this way, Elias strives to overcome the shortcomings of, on the one hand, methodological individualism, and, on the other hand, the shortcomings of sociological macro theories that emphasize the importance of macrostructures. Each actor is part of a complex network of interrelations (figurations), but at the same time, each actor constantly changes figurations through his actions.

Instead of structures that act as external forces that direct the behavior of individuals, figurations, which are in a constant process of change, create networks of interdependence that shape the consciousness and activities of individuals, but these figurations are in a constant state of change due to actors. Elias emphasizes that the way in which figurations will develop, most often, is not a product of the targeted activity of actors, but a product of spontaneous development, which is not predictable. The goal of process sociology is to discover the sequential order of development of figurations throughout history. Such development of figurations in Western Europe was the focus of his books The Court Society and On the Process of Civilization.

Process of Civilization

In the The Court Society, Elias studies the process by which the chivalrous aristocracy, as it existed during the Middle Ages, with the emergence of an absolute monarchy in France during the reign of Louis XIV, was transformed into a refined nobility. In that period, the feudal aristocracy, which was in constant conflict, became part of the court society under the control of the absolute ruler. Instead of an open conflict with the king, aristocrats become part of the court elite who fight among themselves to achieve prestige and power within the court hierarchy. Achieving the highly prestigious status of the aristocracy was closely related to extravagant spending, which confirmed its position.

In the two-volume book On The Process of Civilization: Sociogenetic and Psychogenetic Investigations, Elias expands his research by studying how the rules governing the behavior of the aristocracy spread to wider strata of society. The spread of these rules of conduct is the essence of the process of "civilizing" Western European societies. The civilizing of society takes place on two levels, on the one hand, aggressive behavior between people is suppressed, while on the other hand, there is the development of very precise rules that regulate individual behavior. Control over individual behavior refers, above all, to the adoption of the rules of good behavior in social situations - the rules of etiquette.

The first volume of this book deals with the adoption of etiquette rules and is called The History of Manners. Elias follows the development of rules that regulate many areas: eating behavior, the way physiological functions are performed, regulation of sexual behavior and gender relations, and the like. He calls this process the "sociogenesis" of civilization. The rules of good behavior are adopted on the cognitive and behavioral levels by individuals. The main change on the individual level is an increase in the feelings of shame and anxiety concerning one's own body and satisfying the most basic biological needs. Behavioral changes are directly related to changes in the structure of the wider society. When the aristocracy became part of the court society, individuals from the aristocracy came to a state of greater physical closeness, but also greater interdependence.

To avoid conflicts, rules of good behavior were created that controlled the behavior of the aristocracy. With the declining rigidity of class stratification, people from different strata increasingly came into close physical contact and interdependence. Thus, there was a need to extend the rules of good behavior to the lower strata of society; first to the bourgeoisie, and then to other strata. Behavioral rules become part of the "habitus" that individuals adopt from birth and throughout life. This shaping of the mentality and behavior of the individual is a process of "psychogenesis".

In the second volume of On the Process of Civilization, subtitled State Formation and Civilization, the focus of research shifts to changes at the macro level and the process of "sociogenesis", the emergence of a social field that includes not only individual states but also the sequential sequence of evolution of interdependent societies. Over time, people, more and more, adjust their behavior in relation to other people, and to progressively stricter and more precise rules. Each individual action is increasingly regulated, in order to fulfill a certain social function. Behavior is, more and more, regulated automatically, from the earliest age, and it begins to impose itself as a compulsion that is impossible to avoid, even with conscious desire.

On the other hand, the state, headed by an absolute monarch, becomes more centralized and begins to monopolize the use of physical force and tax collection. It is the combination of control over the means of force and over cash flows that gives enormous power to the absolute monarch who imposes rules of conduct on the subordinate aristocracy at his court. The emergence of an absolute monarchy does not depend on the psychological character of the ruler but depends on the development of specific social structures, that is, figurations, which enable the emergence of absolute rule and a centralized state. The development of the division of labor, demographic growth, urbanization, the growth of trade, and the monetary economy, created the conditions for the emergence of an absolute monarchy. First, the war relations between the various feudal lords calmed down, which enabled the progress of the cities and increased the division of labor. In particular, the growth of trade and the monetary economy enabled the monarch to create an independent source of income regarding the feudal estates of the aristocracy. As the economic importance of land ownership declined, so did the economic and military power of the aristocracy.

The development of trade and the monetary economy also enabled the growth of the bourgeoisie, so the absolute monarch used this change in the relationship between the power of the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie, to increase his power even more. The development of centralized power conditioned the increase of administration and bureaucracy, which, together with the increase of the economic power of the bourgeoisie, enabled the emergence of a modern state. The process of development of civilization and civility is long and takes place over several generations. The main change occurred in relation to the source of control over individual behavior. In the Middle Ages, external coercion prevailed, while later, internal, psychological control of the superego began to be the main source of control over individual behavior. Elias did not view this process as positive or negative, but viewed it neutrally and emphasized that arbitrariness in choosing which type of behavior to choose is the basis of good behavior.

Later Works

In his later works, Elias further develops theoretical concepts of process sociology and applies these principles to various fields. In his book The Quest for Excitement: Sport and Leisure in the Process of Civilization (1986), he connects the development of parliamentarism in Great Britain with the development of sports and other forms of leisure. The process of civilization leads to the routinization of life and boredom, so there is an impetus for the development of activities aimed at de-rutinizing life and creating a sense of belonging and identity, as well as excitement and entertainment. The upper classes developed their own leisure activities such as arts and fox hunting, while the lower classes began to engage in and follow sports activities. In the book Studies on the Germans (2013, in German 1989), Elias explores the psychogenesis and sociogenesis of the German state. He found that the German national habitus was focused on militarism, which provided the basis for the later rise of the Nazi Party.

The book What is Sociology? (2012, in German 1970) Elias provides more arguments in favor of the development of sociology that will abandon the idea of homo clausus and embrace the idea of the open man and the importance of studying relational connections between people. Individual psychology and the way we see the world arises from the figurative matrices of which people are a part. Elias believes that philosophical epistemology, from René Descartes to phenomenology, has identified the consciousness of Western European men, whose consciousness is shaped by a specific habitus, with the consciousness necessary to create a universal theory of knowledge.

In the books Involvement and Detachment. Contributions to the Sociology of Knowledge I (1987, in German 1983), An Essay on Time: Contributions to the Sociology of Knowledge II (1991, in German 1984), and The Symbol Theory (1991), Elias develops his own sociology of knowledge. Earlier phases of social development were characterized by animistic, magical, and mythical ideas and feelings, as well as the great "involvement" of the person in these fantastic ideas and performances. Over time, there was a gradual development of "detachment", which enabled the creation of knowledge that could more adequately describe and control the forces of nature. On the other hand, the social sciences have failed to separate themselves from the "social forces" that continue to shape those sciences. Elias advocates for the development of scientific procedures and conventions that would isolate knowledge about society from social forces and enable the creation of practical sociological knowledge.

Fields of research

Actors Aggression Animism Art Body Bureaucracy Capitalism Capitalist Class Caste Character, Social City Civilization Classes Community Conflict Control, Social Demography Economy Elites Everyday Life Feudalism Habitus History Identity Inequality, Social Magic Monarchy Morality Motivation Myth Politics Power, Political Psychology Science Sex Sign and Symbol Sports State Status Time Violence Fascism AristocracyTheoretical approaches

Figurational Sociology (Process Sociology)Main works

Über den Prozeß der Zivilisation (1939);

Die Gesellschaft der Individuen (1939);

The Established and the Outsiders: A Sociological Enquiry into Community Problems (1965);

Die höfische Gesellschaft: Untersuchungen zur Soziologie des Königtums und der höfischen Aristokratie (1969);

Was ist Soziologie? (1970);

Über die Einsamkeit der Sterbenden in unseren Tagen (1982);

Scientific Establishments and Hierarchies: Sociology of the Sciences Yearbook 1982 (1982);

Engagement und Distanzierung: Arbeiten zur Wissenssoziologie I (1983);

Über die Zeit: Arbeiten zur Wissenssoziologie II (1984);

Humana conditio (1985);

Quest for Excitement: Sport and Leisure in the Civilizing Process (1986);

Studien über die Deutschen: Machtkämpfe und Habitusentwicklung im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert (1989);

Über sich selbst (1990);

Mozart: Zur Soziologie eines Genies (1991);

The Symbol Theory (1991);

Works translated into English:

Early Writings (2005);

The Court Society On the Process of Civilisation (2005);

What is Sociology? (2012);

The Loneliness of the Dying and Humana Conditio (2010);

Involvement and Detachment (2007);

An Essay on Time (2007);

Studies on the Germans (2013);

Mozart and Other Essays on Courtly Art (2010);

The Symbol Theory (2011);

Essays I: On the Sociology of Knowledge and the Sciences (2009);

Essays II: On Civilising Processes, State Formation and National Identity (2008);

Essays III: On Sociology and the Humanities (2009);

Interviews and Autobiographical Reflections (2013);

Studies on the Germans (2013, in German 1989);

Supplements and Index to the Collected Works (2014).