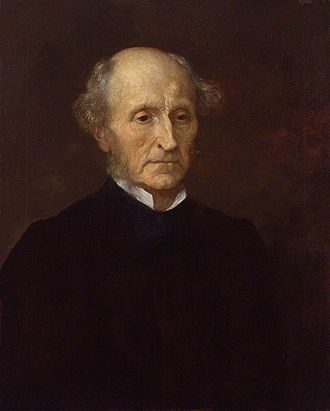

Mill, John Stuart

Bio: (1806–73) British economist and political philosopher. John Stuart Mill was the son of the famous and influential British economist James Mill and was educated in his early years by his father. John S. Mill didn’t attend university but started working for the British East India Company in 1823 (where his father also worked). He stayed with the company until it was nationalized by the British state in 1858. Mill served as lord rector of the University of St. Andrews from 1865 to 1868. In that period, he was also an independent member of the UK Parliament. Even though Mill had a short academic career he was one of the most famous and influential British economists and political philosophers of his time. He contributed immensely to areas of political economy, political philosophy, epistemology, and methodology of social sciences. In his writing, he dealt with various topics: democracy, law, women’s rights and feminism, international trade, labor theory, poverty, psychology, mathematics, religion, and theology.

Epistemology and Methodology of Social Sciences

James Mill (father of John Stuart Mill) was a follower and collaborator of Jeremy Bentham, who developed a philosophical approach known as utilitarianism. Bentham and Mill’s father James used the logical tool of deduction to understand, explain, and model social phenomena. John Stuart Mill, in his book A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive (1843), rejected this approach to social sciences. In this book, Mill introduced his analysis of methods appropriate for studying different scientific fields. He concluded that there are differences between physical and social sciences and that the deductive approach, while suited for physical sciences, wasn’t adequate for social sciences. To explain his position Mill analyzed two alternative methods, which he called the geometric and the chemical. His father used the geometric method when he wanted to, starting from several stated axioms related to human selfish motivation, deduce the optimum form of government. John Stuart Mill argued that his father was wrong in his approach because social and political reality is far more complex, where multiple conflicting forces have their influence. This lack of uniform determinism prevents the use of deduction in scientific analysis of society. The chemical method entails using observation and deduction to infer causal laws in complex systems (like chemistry) that are in some systemic way related to underlying physical causes. But the limitation of this method is that can only be applied to those systems that are invariantly related to underlying causal relations, which is not the case with society, economy, and politics. Mill argues that ‘true’ causation only exists on the level of local physical events, and that human society and economy are too far removed from that type of causality and simplicity of relations. Only an eventual understanding of the causal laws that function at the level of physiology can, in the future, lead to the application of physical methods to social sciences and the unity of physical and social science.

Mill also argued that the application of experiments to social, economic, or political phenomena is not possible because it is not feasible to set two identical situations with only one factor, the impact of which we want to study, being different. This line of reasoning leads Mill to conclude that neither deduction nor experiments and observation, when applied to society and politics, can produce any reliable causal relations or regularities. Since knowledge about society, politics, and economics can’t come from experience, it must be built on introspection. Method of using introspection to understand human character and motivation Mill called ethology. Using ethology and empirical induction is the only way to understand the social world. This method does not produce full causal knowledge but can produce ‘empirical laws’ that have various levels of range and accuracy. Mill, following Comte's distinction, surmises that empirical laws that are produced by this method lead to knowledge about social statics or ‘uniformities of co-existence’, and social dynamics or ‘uniformities of succession’.

Economics

John Stuart Mills's approach and theories about the economy were shaped by the works of Thomas Malthus (1766–1834), David Ricardo (1772–1823), Adam Smith (1723–1790) and his father’s work. Mill studied various economic topics - taxation, international trade, wages and profit, the division of factors of production, and competition. He viewed economics as an inseparable part of social philosophy, and as a science that needs to apply both deductive and inductive reasoning.

Mill’s seminal work on economy is Principles of Political Economy (1848), which went through numerous editions, and was influential and was used as an essential textbook for economic teaching in England for a long time. In this book, Mill analyzed the potential for economic growth in the future and presented four possible scenarios for it. In the first scenario, economic development unfolds in line with the predictions of Robert Malthus – population growth outpaces the growth of capital and technology which results in lower wages and standard of living for ordinary workers and higher profits for capitalists. The second scenario reflects Adam Smith’s predictions – capital accumulates faster than population growth which leads to higher wages and standard of living for workers.

The third scenario follows the reasoning of Ricardo and envisions a situation where the supply of capital and the growth of the population increase at the same rate, but technological development lags. In this case, the supply of labor and the demand for it will increase at the same rate, so the real wages will stay the same. Lack of technological development will lead to increased use of inferior agricultural land to feed the growing population. Rising food and rent prices will cause a reduction in profits. Mill argued that is the most likely scenario to happen. In the fourth scenario, technological development supersedes the growth of both capital and population, leading to lower wages, rents, and food prices, higher profits, and the overall growth of the economy.

Mill analyzed international trade and concluded that the countries with lower demand and greater elasticity of demand would benefit the most from this trade. When demand is elastic changes in prices of imported goods inversely influence the volume of imports – the higher the prices, the lesser the demand, and the other way around. Mill was the first economist that introduce this relationship between the prices of goods and demand for them.

Mill developed the concept of opportunity cost, which refers to the inherent cost, whether it is financial or another type, associated with some action or a choice. For example, choosing to have a child, for an employed woman, may not only include the cost of raising the child but also the loss of earnings and delayed advancement in the profession. Mill rejected the classical wage fund doctrine and argued that both worker’s wages and the company’s total wage fund are more flexible than previously thought.

Political Ideas

Mill’s political ideas were influenced by the works of Auguste Comte, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Jeremy Bentham, David Hume, Adam Smith, Adam Ferguson, Wilhelm von Humboldt, and Alexis de Tocqueville. From Comte, he took the idea of history as a progress of rationality and believed that British society was on the verge of transitioning into the organic period, in which more rational institutions would replace inefficient bureaucracy. He believed his work was needed to push Britain into the organic period. Tocquevill’s two volumes of Democracy in America warned him of the dangers of the potential of mediocracy, uniformity, and conformism to prevail in an egalitarian democracy where everybody would have the same right to vote and choose. Historical research done by Smith, Hume, and Ferguson convinced Mill that, to understand social and political institutions, one must understand their historical development. From Coleridge and Humboldt Mill took the Romantic ideals of individual development and fulfillment. Mill further developed and revised the philosophical and political ideas of Bentham’s utilitarianism.

Liberty

In the book On Liberty (1859) Mill proposed what he called a very simple principle, which refers to the notion that the government cannot impose any restrictions on individual freedom and liberty apart from preventing someone from causing harm to others. This principle also states that the state has no right to introduce no restrictions on an individual’s behavior to protect his moral or physical wellbeing. Mill wanted for society and individuals to achieve moral progress, although not by coercion but through liberty, as freedom of speech and thought can bring about innovation, experiments, and new ideas and thus create new social forms, new forms of domestic life, and new types of economic organization. This would ensure that society overcomes mediocrity and stagnation. In that way, liberty ensures the greatest utility for everybody.

Government

In Considerations on Representative Government (1861) Mill expands on ideas introduced in On Liberty, showing how positive organization of political institutions can embody and promote the utility of liberty. He introduced two criteria for judging government and its institutions – education and efficiency. Efficiency ensures the optimal use of good qualities in people, while education promotes the rise of those good qualities. In the book, Mill analyzes how best to balance between education and efficiency in different political institutions. Concerning the right to vote, he reasoned that everybody has to have the right to vote, to ensure that their interests are protected and represented. But, on the other hand, he was opposed to secret voting, because public voting would prevent selfish behavior and necessitate voters to justify their choices based on reason and social utility. Mill also advocated for plural voting for educated and professional individuals, and the implementation of education tests as a condition for the right to vote. He argued that new legislation should be created by commissions of experts, and not by elected representatives. Mill distinguished between True democracy and False democracy. In True democracy, voters are encouraged to use reason in making political decisions but are prevented from making unreasonable decisions. The ultimate goal of the government is to help individuals develop their own path to happiness, although everyone is responsible for creating that path and achieving happiness.

Utilitarianism

As mentioned earlier, Mill was a follower of Bentham’s philosophy of utilitarianism. Bentham’s utilitarianism was shaped by three defining ideas: the principle of the greatest happiness, universal egoism, and the artificial identification of someone’s interests. Mill, in his book Utilitarianism(1863), made important modifications to Bentham’s utilitarianism. Mill argued that knowledge of social and historical context that shaped some social institution is needed to judge the utility of that institution. Other alteration to the principle of utility concerns the possibility of distinguishing between higher and lower qualities of pleasure. As pleasure is the source of happiness and utility we need to study both the quality and quantity of different pleasures to determine the greatest utility for an individual. Mill sees altruism, higher feelings, and intellect as some of the important sources of higher pleasure. While Bentham studied utility from the point of the individual, to regulate individual actions, Mill argued that the principle of utility should be used on the level of society, to shape its practices and institutions. Mill stated that utility shouldn’t replace conventional morality.

Right of Women

Mill, influenced by his longtime friend and later wife, Harriet Taylor, wrote The Subjection of Women (1869). In this book, radical for its time, Mill argued for women’s rights and overall equality for women and their self-development. Cultural rules are used to subjugate women and limit their development. Allowing women to join the workforce and other social positions would lead, not only to the liberation of women but also to the progress of society as every position in society would be filled by the most qualified person. As a member of parliament, Mill tried to amend the 1867 Reform Bill, which was passed and extended voting rights, to include an amendment that would grant voting rights to women but was eventually unsuccessful.

Capitalism and Socialism

Mill’s political ideas about the best economic system gradually developed over time as, in his early years, he was a proponent of Adam Smith’s laissez-faire liberal organization of economy, as he thought that it gives the best conditions for individual self-development. In his later years, he became much more sympathetic to some economic ideas promoted by socialism which is evident in later revisions of his book Principles of Political Economy, and in posthumously published Chapters on Socialism (1879). Mill concluded that a laissez-faire economy didn’t allow for everybody to realize their full development, freedom, and utility. He began to see the rise of a cooperative type of firms as a chance to evolutionary overcome the deficiencies of capitalism, by lessening inequalities and promoting moral progress and a better form of individuality. Mill was still fearful of the realization of full socialism, as it entailed too much centralization and bureaucratization of the economy.

Fields of research

Actors Altruism Atheism Bureaucracy Capitalism Christianity Civil Society Colonialism Conformity Cooperation Cooperatives Culture Democracy Economy Education Gender History Human Rights Individualism Industry Industrial Democracy Innovation Institution and Organization Knowledge Law Leaders Liberalism Market Morality Motivation Politics Rationality Religion Science Social Policy Socialism State Technology Tradition Voting WorkMain works

Civilization (1836);

A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive (1843);

Essays on Some Unsettled Questions in Political Economy (1844);

Principles of Political Economy (1848);

On Liberty (1859);

Considerations on Representative Government (1861);

Utilitarianism (1863);

England and Ireland (1868);

The Subjection of Women (1869);

Autobiography (1873);

Three Essays on Religion: Nature, the Utility of Religion, and Theism (1874);

Socialism (1879).