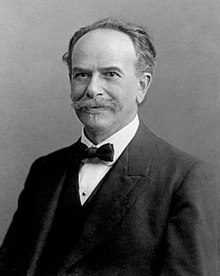

Boas, Franz

Bio: (1858–1942) German-American anthropologist. Boas studied natural sciences and geography and got his Ph.D. in physics at the University of Kiel, but soon after that turn his attention to ethnography and anthropology. In 1885 he become an assistant at the Museum of Ethnology in Berlin and later moved to the USA where his first academic appointment was at Clark University in 1888. In 1896, Boas became curator of the American Museum of National History in New York. In the same year, he started lecturing at Columbia University, where he stayed for the rest of his career. He modernized the journal The American Anthropologist and helped to found the American Anthropological Association in 1902. Boas edited the Journal of American Folklore from 1909 to 1925. Boas also pioneered the use of new technologies like the photography of phonographs. Boas is recognized as the “father of American anthropology” because at Columbia University he trained many students who become famous anthropologists in their own right and because he helped turn anthropology into a well-rounded four-field discipline, and that division – linguistic anthropology, archaeology, biological anthropology, and cultural anthropology – is still widely used.

Boas built his approach to anthropology known as historical particularism or historical relativism (both are names given to his approach by others). He stressed that researchers should have a good command of the native languages so they can directly understand what people were saying and that they should collect and collate all types of data. He was also skeptical about classifications, and hypotheses based on generalizations in anthropology. He preferred using classifications that people who were studied used themselves. Data collected in the field should speak for itself and it shouldn’t be pushed into pre-conceived classifications and theories. His “historical particularism” method was based on rejection of deductive logic and the adoption of the inductive method.

Boas rejected theories of socio-cultural evolutionism like those of Henry Morgan or Herbert Spencer. These theories ranked cultures on different stages of evolutionary progress and presupposed the coincidence of language, culture, and biological heritage. Boas, in turn, in his research showed that language, culture, and biological heritage varied independently of each other. The evolutionary and comparative methods were flawed because, per Boas, because similar cultural characteristics (customs, beliefs) could have different origins in different cultures. For Boas, every culture could be understood only with respect to its own historical development, and that development is accidental and doesn’t follow any predetermined evolutionary path of development. That’s why his approach is called “historical particularism” or “Boasian nominalism”. His cultural relativism and particularism also stated that explanations of individual rationality should be done in relation to cultural goals and strategies and environmental conditions of societies where those individuals lived.

Boas conducted several field research on native communities of the Pacific Northwest, especially with Kwakiutl people, where he studied their language, kinship, and the practice of “Potlach”. Potlach was a group redistributive ceremony in which wealth war exchanged for credit and obligations, but also served as a source of prestige. Boas compared this form of wealth exchange to the modern banking system and found it not too dissimilar.

Boas studied the concept of race and found that racism, specific history, and environment could explain all differences and diversity between different populations and that biological differences play an insignificant part in it. Boas, as a part of a major project for the U.S. Immigration Commission, published the book Changes in Bodily Form of Descendants of Immigrants (1912). In that study he compared bodily measurements of 18 000 immigrants and concluded that environment and nutrition played determining roles in the physical attributes of individuals, and that conclusion was very important because racial theories of that time used physical features of people, such as head size, to demarcate racial differences. In the book, The Mind of Primitive Men Boas rejected the racist doctrines of Gobineau and Chamberlain. In 1940 he published a selection of his essays in the book Race, Language and Culture. Boas rejected all forms of racial prejudice and was critical of the official policies of the US and Canadian governments toward black and native people. He also condemned anti-Semitism and wrote about it in the German press before WW II.

Fields of research

Anthropology Communication Community Culture Diffusion Discrimination Education Everyday Life Evolution Group History Human Nature Identity Immigration Language Morality Myth Prejudice Race Rationality Sign and Symbol Status TraditionTheoretical approaches

Historical Particularism (Boasian Anthropology)Main works

Kwakiutl Texts, 3 Vols. (1902-1905);

The Kwakiutl of Vancouver Island (1909);

The Mind of Primitive Man (1911);

Handbook of American Indian Languages (1911);

Changes in Bodily Form of Descendants of Immigrants (1912);

Tsimshian Mythology (1916);

Anthropology and Modern Life (1928);

General Anthropology (1938);

Race, Language and Culture (1940).