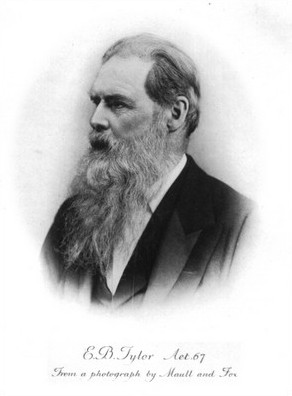

Tylor, Edward B.

Bio: (1832-1917) British ethnologist and anthropologist. Due to his Quaker religion, he was not allowed to study at British universities, hence all of his education was done outside a formal academic system. Tyler became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1871 and received an honorary Doctor of Civil Laws degree at Oxford in 1875. He was given a Readership in Anthropology at Oxford in 1884 and became the first professor of Anthropology at the same university in 1896. Tylor became the first president of the Anthropological Society in 1891. Tylor is regarded as a founder of the science of anthropology and its curriculum, and he significantly expanded the anthropological lexicon.

Tylor traveled to Mexico in 1856 where he befriended ethnologist Henry Christy. Together they studied cultures, people, and artifacts in Mexico. The product of this research was Tylor’s first book Anahuac or Mexico and the Mexicano Ancient and Modern (1861), where he presented the history of Mexico and Aztecs and depicted in detail archeological ruins in Mexico. He also described various contemporary Mexican customs and stressed the cross-cultural similarities. Tylor compared the Mexican custom of the burning of effigies of Judas during the celebration of Easter with the English custom of the burning of the effigies of Guy Fawkes on the November 5th celebration (Bonfire Night).

Universal Evolution

In his later works, Tylor developed his theory of unilinear or systemic evolution. He thought that all societies and cultures go through unilinear developmental stages starting from the small-scale primitive stage of savagery to large-scale civilization. His cultural developmentalism is utilitarian, as he asserts that cultures are created by intelligent people who invent new customs or technologies to solve practical problems and increase their benefit.

In the book Researches into the Early History of Mankind and the Development of Civilisation (1865) Tylor, by analyzing sign language in different cultures, concludes that there is a universal psychic unity in humankind, as all elementary processes of the mind are the same in all societies, regardless of racial, climatic or anatomical differences. The spoken language evolved from sign language, and parallel to it mind evolved from focusing on concrete objects to one focused on abstract ideas. Based on his work on pre-Columbian cultures in Mexico Tyler concluded that the evolution of symbolization in humans started with the earliest writing. In his later writings, he explained the development of grammar in language as a product of human effort to express its thoughts in a clearer and more precise way.

The primitive mind blurs the lines between oneself and others and between object and image and forms the basis of the magic thinking and magic. Tylor divided cultural myths into ‘myths of observation’, which recorded facts, and ‘pure myths’, which are purely fictional. He introduced the concept of survival which denoted vestigial evidence of the complete social and cultural situation that existed in the history of some society. Survivals can be used to reconstruct that previous situation. Rural folklore often contains many survivals that are evolutionary vestiges of the primitive past. Cultural customs that exist as survivals are evidence that customs should be viewed as sui generis phenomena, existing through the power of tradition, long after they had lost the purpose, for which they were invented.

Concerning cultural parallels Tylor posits that most of them are the product of independent invention, but some are also the product of diffusion of cultural patterns. Cultural diffusion is only possible if two cultures are similar enough so the cultural pattern that is transmitted can take roots in the new cultural environment.

Tylor took earlier classifications of evolutionary stages into savagery, barbarism, and civilization and applied them to his theory. Based on archaeological and historical research of technological inventions and technological progress all over the world Tyler divided these stages by their major technological developments. Savagery starts with the use of stone tools, barbarism starts with the invention of farming and metallurgy, while civilization begins with the use of writing. Evolutionary progress in the use of technology is in almost all cases nonreversible, that is, once some society invents better technology it does not revert to an earlier lesser form.

Primitive Culture

Tylor’s third book Primitive Culture (1871) had two volumes. In the first volume, Tylor introduces the definition of culture: „culture....is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.” He was the first to define anthropology as the “science of culture”. Tylor stresses that the focus of anthropology, thusly defined, should be on legends, myths, religion, superstitions, and folklore, as they are the most important and abundant source of cultural survivals. Cultural institutions should always be seen in the context of their usefulness to cultural development. Even cultural institutions, like magic, that are the product of the primitive mind that is not able to rationally understand nature, have their usefulness in the evolutionary stage in which they are developed. For example, religious myths and legends are just a symbolic expression and justification of social relations.

In the second volume of the Primitive Culture, using the comparative method on data collected from all over the world, Tylor researches the development of religion and religious thought from its earliest stage of animism to the most abstract religion of Protestantism. Animism is the earliest and most primitive form of religion, and is the product of a conscious attempt of people to answer some of the most important questions – the meaning of life, what happens after death, what is the relationship between dreams and reality, is there a soul, etc. Primitive people interpreted dreams and concluded that there exists the soul (anima in Latin) and the ghost soul. Living things have souls, while dead things have a ghost soul. The mind of the primitive people living in the stage of savagery is childlike, as it is preoccupied with imagination and is unable to make a distinction between what is real and what is imaginary. The soul represents the duality of life – separation of spirit from the body, dreams from reality – and is the universal answer to previously mentioned questions. In the religious practice of animism, all things in nature (animals, plants, and physical objects) possess supernatural force (soul) and the focus is on winning over and controlling those supernatural forces. Religious practices and beliefs like ancestor worship, reincarnation and guardian spirits, fetishism, and idolatry are the next evolutionary stages and are logical descendants of animism. The next stage in the evolution of religious thought is polytheism, which is even more abstract, where humanity and nature is divided into hierarchies.

The next stage would be the ascribing of doubles to animals as well as humans, as attested by the placing of horses or cats in tombs, and then to objects (an object’s double would be used in the next world by the deceased). The cult of manes, divine or daemonic creators of souls, is a further stage leading to a belief in souls existing in certain individuals and ancestors (the cult of saints in modern religions would be a survival of the latter). This is followed by the cult of spirits, known as fetishism before souls are ascribed to objects (idolatry). The final stage is the most monotheism with Protestantism being the most abstract religious practice. It is important to note that atavistic survivals from previous stages are always present, with the revival of spiritualism in Victorian Britain as one of the best examples. Taylor sees all religions as a form of logical, but flowed folk philosophy.

Later Works

Tylor’s Anthropology: An introduction to the study of man and civilisation (1881) is a textbook of anthropology that expounds on all areas of culture, and, in its closing part, investigates the benefits and risks of revolutionary transformations happening in modern civilization. It was the most influential and widely read anthropology textbook for decades after it was published. In the article ‘On the Methods of Investigating the Development of Institutions Applied to Laws of Marriage and Descent’, Tylor advocates for anthropology to adopt a method similar to that of natural sciences. In this article, he deployed a comparative method to analyze correlations between residence and descent (matrilinear or patrilinear) and couvade (custom when a man is performing ritualistic “labor” of a child in public, while his wife is giving birth for real outside public view) for 350 societies. Tylor showed that there is a wide correlation between exogamy, cross-cousin marriage, and classificatory terminologies. Rules of exogamy and marriage served an invaluable function in preventing societies from dying out.

Fields of research

Agriculture Animism Anthropology Civilization Communication Culture Customs, Social Death Diffusion Economy Evolution Family Game Human Nature Innovation Kinship Knowledge Language Magic Matriarchy Myth Nonverbal Communication Patriarchy Personality Race Rationality Religion Sign and Symbol Technology TraditionTheoretical approaches

EvolutionismMain works

Anahuac, or Mexico and the Mexicans (1861);

Researches into the Early History of Mankind and the Development of Civilization (1865);

“The Religion of Savages”, in Fortnightly Review (1866);

Primitive Culture: Researches Into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art and Custom, 2 vols. (1871);

„On the Game of Patolli in Ancient Mexico, and its Probably Asiatic Origin”, in Journal of the Anthropological Institute (1879);

Anthropology: An Introduction to the Study of Man and Civilization (1881);

“On a Method of Investigating the Development of Institutions; Applied to Laws of Marriage and Descent”, in Journal of the Anthropological Institute (1889).