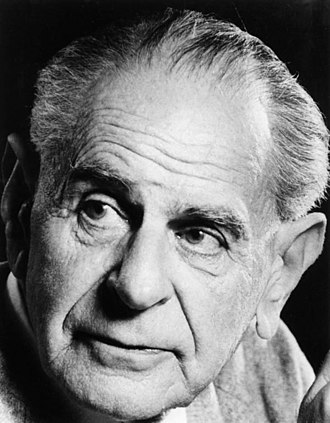

Popper, Karl Raimund

Bio: (1902–94) Austrian-British philosopher. Karl Popper studied mathematics, physics, philosophy, and psychology at the University of Vienna. Popper wrote his Ph.D. thesis On the Methodology of the Psychology of Thinking under the advisory of Karl Bühler. After he got his Ph. D. Popper became a teacher in Vienna. Popper emigrated to New Zealand in 1937 and got a lectureship at Canterbury University College there. In 1946 he moved to Great Britain and undertook a readership in ‘Logic and Scientific Method’ at the London School of Economics. He later became a professor there and stayed until retirement. Popper became extremely famous and respected in Britain so much that he was knighted in 1965 and became a member of the Royal Society in Britain.

Popper’s education and writing were influenced by his University of Vienna professors - Karl Bühler, Alfred Adler, and Heinrich Gomperz. Popper worked as an assistant of Alfred Adler and got inspired by Adler’s ‘individual psychology’ to study psychology, but under the influence of Gomperz Popper shifted his focus from psychology to the philosophy of science. Popper adopted Bühler’s theory that language has three functions - expressive, communicative, and descriptive – and added the fourth – argumentative. The most important intellectual influence on Popper’s work was by a group of philosophers gathered around Moritz Schlick, informally known as the Vienna Circle. The Vienna Circle included several notable philosophers - Rudolf Carnap, Otto Neurath, Herbert Feigl, Karl Menger, Hans Hahnand, and Friedrich Waismann. They developed an epistemological approach called logical positivism, which was a version of empiricism that used modern mathematical logic.

Epistemology and Philosophy of Science

Popper is best known for his work on epistemology which was elaborated in the book The Logic of Scientific Discovery (1959) (this is a translation of a revised and expanded version of Popper’s book Logik der Forschung, published in German in 1934). In The Logic of Scientific Discovery Popper moves away from the logical positivism of the Vienna Circle. While logical positivism stressed the importance of empirical verification of scientific theories, Popper introduced the notion of falsification and claimed that it is the only way to truly determine whether some theory is scientific or not. According to Popper, scientists should propose theories that are designed in a way that they are easiest to refute i.e., shown to be false, by experimental or observational evidence. In order to verify the statement „all swans are white“scientists would need to check every swan that has ever existed, which is impossible, but, on the other hand, to falsify that statement scientists only need to find one swan that is not white. If attempts to falsify a theory fail that leads to the corroboration of that theory. The goal of experimental scientists should be to try to either falsify or corroborate a theory. Popper warns that theories shouldn’t be protected, or as he says immunized, from falsification by the introduction of ad hoc hypotheses. Logical positivism was based on inductive logic, while the process of falsification follows deductive logic.

We cannot distinguish science and non-science based on the methodology used to come to conclusions, because all empirical observations are fallible, selective, and conditional, hence we can only corroborate them if they prove not to be false. In that sense, science does not produce universal laws, but can only produce a large body of evidence that supports some generalization. All scientific statements are provisional and subject to the process of “conjecture and refutation”. Theoretical progress in some scientific fields consists of constant revisions of existing theories, rejecting falsified ones and supplanting them with more encompassing theories. Popper rejected the theory of scientific revolutions proposed by Thomas S. Kuhn.

Popper strongly argues that theory or even whole theoretical approaches that cannot stand the process of falsification belong to the field of metaphysics. He thinks that psychoanalysis and Marxism belong to the category of pseudoscience as they purport to explain everything so they can’t be falsified. Popper does not reject all metaphysics as some beliefs, as those that state that nature is uniform and follows the rules of causality, although not falsifiable, are useful for science.

Popper replaced the concept of falsification, in his later work, with the broader concept of “critical examination” that could be applied not only to scientific but also to metaphysical claims. This approach became known as “critical rationalism”. Popper also explored the body-mind dualism and concluded that there exist three worlds. The first world consists of the objective reality of physical objects, the second world consists of subjective, mental phenomena like ideas and emotions; while the third world is composed of phenomena that are at the same time both objective and mental–cultural products that reach autonomy from individual minds (language, art, religion, law, institutions, etc.

Social Philosophy

Popper introduced his social and political philosophy in two books published around the same time - The Poverty of Historicism (1944) and The Open Society and its Enemies (1945). In The Poverty of Historicism, he attacks historicism as a flawed approach to socio-historical development propagated by authors like Plato, Hegel, and Marx. They developed seemingly objective laws of inevitable historical development that follow the strict path to some historical destiny or a predetermined end, that cannot be altered by actions of the individuals. On the contrary, Popper argues that those theories are not scientific as they are teleological and not falsifiable as they are purposefully vague and that sociology and history can only discover some social trends and not general laws. History is shaped mostly by unplanned individual interactions that lead to unforeseeable results, as a multitude of unknowable factors can influence any single event. Even the very act of predicting the future can influence the future to change as people can act differently when they know the prediction when compared to how they would act not knowing that prediction. In explaining single historical events scientists can only use what Popper calls the “logic of a situation” where we treat individuals as rational and purpose-oriented subjects acting in a specific social situation.

In The Open Society and its Enemies Popper uses his logical method of falsification to explore what type of society is the optimal and provides most freedoms. He argues that theories of the organization of the state and society championed by authors like Plato, Hegel, and Marx are antithetical to freedom as they favor collectivistic and organismic whole and represent philosophical precursors of political totalitarianism. All those ideas about radical social transformations have two great deficiencies, first, they require for unelected minority with supposedly superior knowledge to impose their will on everybody else, at second social arrangements they propose may lead to unintended and unforeseen negative consequences that are hard to correct. In place of those kinds of radical social transformations Popper strongly argues for a “piecemeal social engineering,” i.e., incremental improvements that are easily controlled and are able to be amended. This trial-and-error model of social improvement can be subjected to a falsificationist form of social research, which allows society to correct unforeseen and undesirable effects of changes. Instead of using the positive utilitarian principle of maximization of happiness, he proposes using the “negative utilitarian” principle of minimizing suffering. In a similar vein Popper suggests that we should forgo the traditional question “who should rule” and replace it with the question of how to minimize the risk of bad rulers coming and keeping their power. Another prerequisite for a good government and open society is having individuals who are personally responsible for their decisions but are also able to effectively criticize and influence the government and regulations.

Main works

Logik der Forschung (1934);

The Poverty of Historicism (1944);

The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945);

"Indeterminism in Quantum Physics and in Classical Physics”, in British Journal for Philosophy of Science (1950);

The Poverty of Historicism (revised edition, 1957a);

“Probability Magic, or Knowledge out of Ignorance”, in Dialectica (1957b);

Logic of Scientific Discovery (translation of revised and expanded version of Logik der Forschung) (1959);

“The Propensity Interpretation of Probability “, in British Journal for Philosophy of Science (1959);

Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge (1963);

Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach (1972);

“Replies to my Critics”, in P. A. Schilpp (ed.) The Philosophy of Karl Popper (1974);

Unended Quest: An Intellectual Autobiography (1976);

The Self and Its Brain: An Argument for Interactionism (1977);

Die beiden Grundprobleme der Erkenntnistheorie (1979);

The Open Universe: An Argument for Indeterminism (1982);

Quantum Theory and the Schism in Physics (1982);

Realism and the Aim of Science (1983);

A World of Propensities: Two New Views on Causality and Towards an Evolutionary Theory of Knowledge (1990);

In Search of a Better World: Lectures and Essays from Thirty Years (1992).