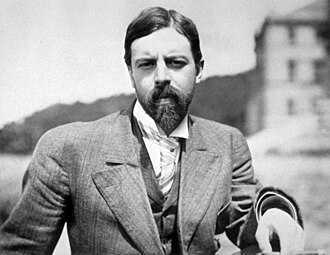

Kroeber, Alfred Louis

Bio: (1876–1960) American anthropologist and archeologist. In 1901 Kroeber got his PhD in anthropology under the tutelage of famous anthropologist Franz Boas. His dissertation, “Decorative Symbolism of the Arapaho”, was based on three months of ethnographic fieldwork with American native people called Arapaho. Kreober spent his whole career in the Anthropology Department at the University of California, Berkeley, where he also became director of the Museum of Anthropology.

Kroeber did ethnographic and archeologic fieldwork throughout the Americas - Peru, Oregon, central Plains, northwest coast of America – but his most extensive and long-term work was with Native Americans in California. Kroeber was also notable for contributing to all four subfields of anthropology: socio-cultural anthropology, linguistic anthropology, physical/biological anthropology, and archaeology. He produced and compiled vast ethnographic data on languages and kinship classifications, but he also developed his own theoretical approach to the concept of culture. Kroeber greatly contributed to the institutionalization of anthropology as a university-based discipline.

Work on Native People of California and New Mexico

Most of Kreober’s early work was focused on native peoples of California and New Mexico, producing a large body of archaeological, ethnological, linguistic material and physical anthropology data, which is evident in the books and articles like The Arapaho (1902), “Decorative Symbolism of the Arapaho” (1901), “Notes on California folk-lore” (1908), “Classificatory Systems of Relationship”, (1909), Zuni Kin and Clan (1917b), and Handbook of the Indians of California (1925b). In the article “Classificatory Systems of Relationship” Kreober denounced Morgan’s theory that kinship terminology reflects the social system, and his classification of kinship terminologies, which divided them into descriptive and classificatory systems. Kroeber introduced a new classification of kinship terminologies based on eight criteria: 1) whether distinction between persons of the same or different generations exists, 2) whether there is a distinction between collateral and direct relationships between relatives, 3) whether age distinctions within a single generation exists, 4) is the gender of the relative known, 5) is the gender of Ego known, 6) is the gender of the person that connects the relatives known, 7) whether the distinction between relatives by marriage and blood relatives is stated, and 8) what is the status of the person that connects the relatives (married or unmarried, dead or alive, etc.). Kreobers data showed that Western kinship terminology often employed fewer criteria than languages of American native groups.

In the book Zuni Kin and Clan (1917b), Kroeber researches the matrilineal kinship system and social organization of the Zuni people from New Mexico. The book explores various topics: marriage, mythology, inheritance, the role of kinship in society, etc.

The Concepts of Culture and Culture Areas

Kroeber perceived anthropology as a humanistic discipline and focused on history and culture while rejecting predictive, deterministic, and causal explanations. His approach could be designated as ideographic, as he viewed causes of cultural and social change as byproducts of the inherent nature of phenomena and specific historical development. Kroeber viewed cultures as total systems of human behavior. Every single culture should be viewed holistically – understanding how all features of a culture relate to one another - and in terms of cultural relativism, as every feature of a culture has meaning only in the specific context of that culture. The goal is to research the natural history of some culture in its totality. Kroeber rejected, what he called, reductionism, that is, explanating cultures and cultural phenomena using biological and psychological explanations.

In the article “The Superorganic” (1917a), Kroeber introduced a three-tiered hierarchy of the fields of scientific inquiry: inorganic, organic, and superorganic. Sciences like physics and chemistry study inorganic phenomena; biology and psychology explore organic phenomena; while disciplines like sociology and anthropology investigate superorganic phenomena. Each level of inquiry has its own specific methods of examination and types of explanation, that are not applicable to other levels. Culture is superoganic meaning that it exists beyond and independent of individual humans. Individuals and individual variations in behavior are inconsequential for describing and understanding specific cultures and changes that they go through.

In addition to using historical method, he also used comparative method to explore cultures, their changes, and cultural creativity. In A Sourcebook in Anthropology (1925), he introduced the concept of culture area, which is associated with a cultural level. The statistical accumulation of crucial cultural elements (e.g. religion, kinship, language) determines some culture’s cultural level, while the level of cultural integrity describes how a certain culture constructs and maintains its cultural level. Kroeber deemed culture to be analogous to grammar, as both were collections of unconscious mental rules and patterns, that allowed him to develop methods for discerning, describing, characterizing, and classifying the cultural elements. This method, in combination with the comparative method, allowed him to determine relations between cultures and group them into different culture areas. In his Cultural and Natural Areas of Native North America (1939) he researched the distribution of cultural elements across indigenous populations of North America and divided their cultures into six large cultural areas and fifty-five regional areas.

In the article “Basic and Secondary Patterns of Social Structure” (1938) Kroeber introduces the distinction between basic patterns of social structure (he later used the term reality culture) that pertain to cultural characteristics related to functional adaptions of a society to its ecological environment, that is, technology, economy, and modes of subsistence, on one hand, and secondary patterns of social structure (he later used the term value culture) that relates to non-adaptive features like art, ritual, and myth. The features of reality culture are causally determined by the environment and exhibit cross-cultural regularities, while features of value culture are non-causal, and independent both from the environment and reality culture and are particular expressions of the cultural creativity of some specific culture.

Kroeber, in Configurations of Culture Growth (1944), employs a historical-comparative approach on a wide scale, analyzing diverse culture areas across the world - China, India, Greece, Islam - and time periods. He explores philosophy, science, art, and literature to discover, what he calls, the high culture, of those culture areas. He uses ethnographic, historical, and archaeological data, and quantitative and qualitative analysis, to identify shared patterns and trends in the cultural evolution between these different cultures. He, also, introduces his concept of cultural configurations, which refers to the idea that cultural characteristics evolve interconnected with broader cultural system.

Kroeber concludes that all of the major civilizations that he analyzed went through the cultural climax, a period of rapid pulse-like growth and innovation, with major advances concentrated within that period. After the cultural climax period of stability and decline follows. Periods of growth are characterized by clusters of geniuses, who are responsible for the majority of cultural creativity in intellectual and artistic fields. The appearance of these clusters of geniuses is the product of the previous cultural development, but once they start to appear they can independently influence the trajectories of the cultural growth. This is, obviously, a deviation from his view in his earlier works, where he rejects the idea that individuals can influence the direction of cultural development.

Kroeber and American anthropologist Clyde Kluckhohn coauthored the book Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions (1952), in which they attempted to systematize the different definitions of culture in anthropological literature between 1871 and 1950/1951. They gathered approximately 300 definitions of culture and then divided 164 of them into seven definition groups:1) descriptive, 2) historical, 3) normative, 4) psychological, 5) structural, 6) genetic, and 7) incomplete definitions. Kroeber also coauthored the book The Concepts of Culture and of Social System (1958) with the sociologist Talcott Parsons, and they concluded that anthropology is the study of culture while sociology is the study of social structures.

Main works

The Arapaho (1902);

“Decorative Symbolism of the Arapaho”, in American Anthropologist (1901);

“Notes on California folk-lore”, in Journal of American Folklore (1908);

„Classificatory Systems of Relationship”, in Man (1909);

“The Superorganic”, American Anthropologist (1917a);

Zuni Kin and Clan (1917b);

Peoples of the Philippines (1919);

Anthropology: Culture Patterns & Processes (1923);

A Sourcebook in Anthropology (1925a);

Handbook of the Indians of California (1925b);

“The Culture-areas and Age-area Concept of C. Wissler”, in S.A. Rice (ed.) Methods in Social Science: A Case Book (1931);

Area and Climax (1936);

“Basic and Secondary Patterns of Social Structure”, in Man (1938);

Cultural and Natural Areas of Native North America (1939);

Configurations of Culture Growth (1944);

The Nature of Culture (1952);

Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions (1952)

Anthropology Today: An Encyclopedic Inventory (1953);

Style and Civilizations (1957);

The Concepts of Culture and of Social System (1958).