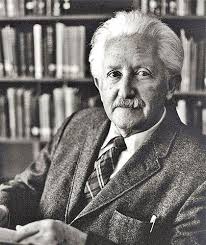

Erikson, Erik

Bio: (1902-1994) German-American psychoanalyst. Erik Erikson, as a young man, tried to become an artist but didn’t have much success. While teaching at a school in Vienna he became acquainted with Anna Freud, the daughter of Sigmund Freud. Inspired by her, he decided to train in psychoanalysis at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute. Erikson also studied the Montessori method of education, where the focus was on child development. He emigrated to the USA and worked as a child psychoanalyst in several hospitals, one of which was Harvard’s Medical School. In 1936, Erikson started working at the Institute of Human Relations at Yale University and taught at the Medical School there. After leaving Yale he taught at Berkeley and Harvard universities. During his career, he did several longitudinal studies on child development, two of which were with Yurok and Sioux Native American people.

Developmental Stages

The primary focus of Erikson’s work, first presented in Childhood and Society (1950), is the question of what is the effect that developmental stages, which are universal for all people, have on the formation of individual identity and personality. Erikson’s theory of developmental stages was inspired by Freud’s theory of psychosexual development but departs from it in several key points. Points of departure are: 1) Erikson’s scheme has eight stages, while Freud’s scheme has five; 2) Erikson’s scheme encompasses all of life’s duration, while Freud’s lasts only up to the end of adolescence; 3) Erikson stresses the greater importance to the development after six years of age; 4) in Erikson’s theory ego plays a very positive and creative role in individual’s development; 5) Erikson emphasizes more interpersonal influences and external environment on the development, while Freud primarily focuses on intrapersonal forces; 6) Erikson doesn’t connect stages with specific erogenous zones on the body, as Freud does.

Erikson’s theory of developmental stages, known also as the configurational approach, took the concept of epigenesis from embryology and applied it to human psychological development. The ego goes through a predetermined sequence of psychosocial stages, with each stage having a separate developmental task of confronting and resolving the unique challenge or crisis. Every challenge presents a new potential for personal growth, and the more successful the resolution of the challenge is, the development is healthier. The creative and conscious ego interacts with its social environment at every stage and tries to resolve the crisis in the best possible way. In earlier stages, the most important environment are parents and their specific child-rearing practice, while in later stages wider society and culture become increasingly more important. Every stage of development is marked by, not only specific crises, but also by corresponding positive and negative emotions, specific social institutional rituals, and specific virtues. The optimal development for an individual entails a balance between the opposite (negative and positive) emotions. In the period before adolescence, the best resolution of the crisis is to integrate mostly positive emotions, while in the later stages, the best resolution is the incorporation of the synthesis of both types of emotions.

At each stage, individuals benefit from experiences provided by significant others, as they help to resolve the tensions between the individual’s psyche and society’s expectations so the positive resolution of the crisis can lead to the adoption of a specific corresponding virtue. Each stage expands from the experience of the previous stages and prepares the person for later stages. The successful resolution of the crisis in one stage is crucial for the success in the next stage. The negative resolution of the crisis can lead to anxiety in later life. Erikson’s configurational approach stresses that the unsuccessful resolution of the crisis in one stage can be remediated by providing better-than-average expectable psychological support in the form of psychotherapy or counseling. The aspect of the theory that states that the outcome of each stage is modifiable ties to the important premise that ego grows throughout someone's life. It is important to emphasize that Erikson’s theory is not completely age-dependent, as crises and challenges of each stage are always present in every stage, only the relative impact they have on the individual varies throughout life.

Table 1. Erikson’s classification of developmental stages

|

Stage |

Age of person |

Positive emotion |

Negative emotion |

virtue |

|

1. infancy |

0 |

trust |

mistrust |

hope |

|

2. early childhood |

1-2 |

autonomy |

doubt/Shame |

will |

|

3. preschool period |

3-6 |

initiative |

guilt |

purpose |

|

4. early school years |

7-12 |

industry/mastery |

inferiority |

confidence |

|

5. adolescence |

13-18 |

identity |

role confusion/identity diffusion |

fidelity |

|

6. early adulthood |

19-30 |

intimacy |

isolation |

love |

|

7. middle adulthood |

31-59 |

generativity |

self-absorption |

care |

|

8. later adulthood |

60+ |

integrity |

despair |

wisdom |

The first stage starts with birth and lasts up to one year of age. In it, emotions of trust and mistrust form the basis of the conflict. The sense of trust is built through the baby’s relationship with its caregivers, that is, if they provide a feeling of physical comfort and a sense of security for the baby. Successful adoption of a sense of trust sets positive expectations for the rest of life, and that is why it is crucial for further positive development in subsequent stages.

In the second stage, conflict is between the need for independence and autonomy, on the one hand, and the sense of shame and doubt, on the other. This conflict stems from the imposition of social rules and self-control (e. i. toilet training) upon the child. Excessive application of rules and punishment leads to the development of a sense of shame and doubt, while positive resolution of conflict ensures that the child will have a strong sense of independence and willpower.

The third stage is marked by the child’s active and purposeful exploration of his or her environment, and the crisis is between taking initiative, and the sense of guilt for taking control over activities. Children in this period are encouraged to take responsibility for their behavior, this leads to the increase of initiative to pursue goals, but also to more challenges, risks, and possible failures. Positive resolution of conflict leads to a sense of purpose in the child, while negative resolution leads to anxiety. In the fourth stage, conflict is between the industry – the ability to focus attention on specific tasks and master cognitive skills – and feelings of inferiority. Positive development at this stage brings curiosity and enthusiasm for learning new things, while negative development results in a sense of inferiority and incompetence.

The crisis of building oneself's identity versus having identity confusion marks the fifth stage of adolescence. At this stage, teens are faced with problems of learning and adopting new adult roles, “fitting in with the group”, and finding out their own path in life. Positive resolution of crisis leads to the building of a stable positive identity and a sense of self based on self-knowledge. Negative resolution of crisis leads to identity or role confusion, that is, the adoption of an identity that was forced upon oneself by peers or parents, and having unexplored social roles and undefined future paths.

In the sixth stage, the primary goal is building healthy relationships with friends and intimate partners, if it is achieved people develop intimacy (ability to love), and if it is not achieved then the result is isolation. The goal of the seventh stage is generativity – the ability to be productive, take care of others, and assist younger generations. Stagnation is the result of the inability to achieve generativity. In the final stage, the goal is to achieve integrity, completeness, and wisdom through a positive retrospective view of lived life. In the opposite case, a sense of doubt, gloom, incompleteness, and despair can overcome a person.

In Identity and the Life Cycle in Psychological Issues (1959) Erikson expands on the theory of life cycle and ego identity, and in Identity: Youth and Crisis (1968) he introduces the concept of identity crisis. Erikson wrote several biographies, or as he calls them psychohistories of influential people from history like Gandhi, Martin Luther (German protestant leader), and Jesus Christ. Although Erikson’s theory focuses on the individual’s adjustment to social rules and expectations, those psychohistories show how people can be adaptive and create healthy identities even in times of radical social transformations, as those are eras in which norms and expectations are rapidly changing. Erikson’s psychosocial approach and concepts of identity and identity crisis influenced several fields of psychology, as well as other sciences and disciplines: sociology, political theory, history, and literature.

Fields of research

Aging Art Authority Body Children Conflict Control, Social Culture Education Emotions Family Health History Human Nature Identity Morality Pedagogy Personality Psychology SocializationTheoretical approaches

PsychoanalysisMain works

Childhood and Society (1950);

Young Man Luther (1958);

Insight and Responsibility (1964);

Identity, Youth, and Crisis (1968);

Gandhi’s Truth (1969);

Dimensions of a New Identity (1974);

Life History and the Historical Moment (1975);

Toys and Reasons: Stages in the Ritualization of Experience (1977);

The Life Cycle Completed: A Review (1982);

Vital Involvement in Old Age (1986).